The HTTP request is the primary interface for client-server interaction over the HTTP protocol. A client sends a request to a server to retrieve data or perform an action. Having a clear request contract reduces debugging time and simplifies integration. It also makes issues easier to locate across methods, headers, and payloads, leading to APIs that are consistent, secure, and easy to use.

What Is an HTTP Request?

An HTTP request is a text-based message a client sends to a server over the Hypertext Transfer Protocol. It specifies which resource the client needs and what operation to perform, and it carries metadata and optional data in headers and body. Every browser navigation, API call, webhook, and microservice interaction relies on this request-response cycle.

HTTP Request Format

Every HTTP request message follows a strict three-part structure defined in RFC 9110: a request line, zero or more header fields, and an optional message body separated by a blank line (CRLF).

POST /v1/orders HTTP/1.1

Host: api.shop.example

Authorization: Bearer eyJhbGciOi...

Content-Type: application/json

Accept: application/json

Idempotency-Key: a3f8c012-7d4e-4b9a-b2c1-5e6f7a8b9c0d

{"customer_id":"c_1024","items":[{"sku":"WH-200","qty":1}]}Request Line

The first line contains three tokens: <method> <request-target> <HTTP-version>.

The method declares intent (read, create, delete), the request target identifies the resource by path and

optional query string, and the version sets protocol framing rules. In HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 the textual request

line is replaced by pseudo-headers (:method, :path, :scheme, :authority),

but the semantics remain identical.

Headers

Headers are case-insensitive key-value pairs that carry metadata about authentication, content negotiation,

caching, compression, and client identity. A single misplaced header — wrong Authorization scheme,

missing Host, or duplicate Content-Type — is often the root cause of 400-level

failures that look like application bugs.

Message Body

The body carries data for methods that modify state, typically POST, PUT, and PATCH.

Its encoding is declared by the Content-Type header: application/json for API

payloads, application/x-www-form-urlencoded for HTML form submissions, and multipart/form-data

for file uploads. Sending a body without the matching content type is the most common cause of 415

Unsupported Media Type errors.

HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 request mapping gotcha

In HTTP/2 and HTTP/3, the textual request line is represented by pseudo-headers such as :method,

:scheme, :authority, and :path. Many edge proxy bugs come from bad

translation between HTTP/1.1 Host and HTTP/2 :authority, especially in multi-tenant

gateways. If routing fails intermittently, compare authority/path values at each hop, not only final application

logs.

HTTP Request Methods

Each HTTP verb carries semantic meaning that affects caching, retry safety, and idempotency. Choosing the wrong

method leads to subtle bugs: retrying a timed-out POST without an idempotency key can create

duplicate resources, while the same retry on PUT is safe by definition.

| Method | Purpose | Has Body | Safe | Idempotent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

GET |

Retrieve a resource representation | No | Yes | Yes |

POST |

Create a resource or trigger processing | Yes | No | No |

PUT |

Replace a resource entirely | Yes | No | Yes |

PATCH |

Apply partial modifications | Yes | No | No* |

DELETE |

Remove a resource | Rarely | No | Yes |

HEAD |

GET without the response body | No | Yes | Yes |

OPTIONS |

Discover allowed methods (CORS preflight) | No | Yes | Yes |

*PATCH can be idempotent if the patch document is designed for it (e.g., JSON Merge Patch), but the

spec does not guarantee it.

HTTP Request Example: GET vs POST

A minimal HTTP request example for retrieving a user profile:

GET /api/users/1024 HTTP/1.1

Host: api.example.com

Accept: application/json

Authorization: Bearer eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1Qi...The server returns a 200 OK response with the JSON representation. No body is sent because

GET is

a safe, read-only method.

A POST request that creates a new user:

POST /api/users HTTP/1.1

Host: api.example.com

Content-Type: application/json

Authorization: Bearer eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1Qi...

{"name":"Jane Doe","email":"[email protected]","role":"editor"}The server returns 201 Created with a Location header pointing to the new resource.

Omitting Content-Type: application/json here causes the server to reject the body or parse it

incorrectly — a mistake that appears in generated clients and test scripts regularly.

HTTP Request Example: Diagnosing a Real API Failure

A common production incident: frontend sends JSON, backend expects JSON, but gateway returns 415

Unsupported Media Type. Root cause is often hidden request formatting drift after a client update.

POST /api/login HTTP/1.1

Host: auth.example.internal

Content-Type: text/plain

Accept: application/json

{"email":"[email protected]","password":"***"}The payload looks like JSON, but the declared media type is text/plain. Changing only one header to

application/json fixes the request. This type of mismatch is frequent in generated clients, CLI

scripts, and test harnesses.

The HTTP Request Lifecycle

Every HTTP request passes through several network and application layers before a response arrives:

- URL parsing — the client extracts scheme, host, port, path, and query string.

- DNS resolution — the hostname resolves to an IP address via recursive lookup.

- TCP connection — a three-way handshake (SYN, SYN-ACK, ACK) establishes the transport layer.

- TLS handshake — for HTTPS, client and server negotiate encryption parameters (one to two extra round trips, or zero with TLS 1.3 0-RTT resumption).

- Request transmission — the client sends the request line, headers, and body over the established connection.

- Server processing — the application parses the request, runs business logic, and builds a response.

- Response delivery — the server returns the status code, response headers, and body.

- Connection reuse or close — HTTP/1.1 keep-alive or HTTP/2 multiplexing allows subsequent requests on the same connection without a new handshake.

When a request fails, identifying which step broke narrows the search. A DNS failure looks different from a TLS

certificate error, which looks different from a 403 Forbidden returned by application logic.

Common HTTP Request Mistakes

- Content-Type mismatch: sending a JSON body with

Content-Type: text/plainor omitting the header entirely. Strict servers return415; lenient ones silently misparse the payload. - Double URL encoding: encoding query parameters that were already encoded, producing

%2520instead of%20. Common when both middleware and application code apply encoding. - Stale auth tokens: a cached

Authorizationheader with an expired JWT causes intermittent401errors that disappear on manual retry because the retry, since the refresh refreshes the token. - Method confusion: using

POSTwherePUTis expected, or calling an endpoint withGETwhen the SDK defaults toPOST. The result is405 Method Not Allowed. - Missing Host header: required in HTTP/1.1, load balancers and virtual hosts cannot route

the request without it. The result is

400 Bad Requestor routing to the wrong backend. - Blind retries on POST: retrying a failed

POSTwithout an idempotency key duplicates side effects — double charges, duplicate orders, duplicate notifications.

Debugging HTTP Requests

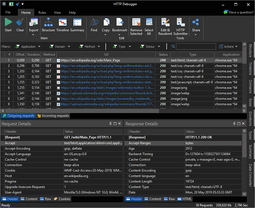

Effective debugging means capturing the exact bytes the client sent, not a reconstruction from application logs. Browser DevTools cover browser requests, but desktop apps, background services, and CLI tools need system-wide traffic capture.

HTTP Debugger Pro captures HTTP and HTTPS traffic across all processes on Windows without configuring a proxy. It decrypts TLS sessions, displays request and response headers side by side, and filters traffic by process name to isolate a single application. The edit-and-resubmit feature lets you change one header or body value and replay the request immediately, confirming whether the fix works before touching any code.DeveloperApplicationWindowsHTTP Debugger Pro screenshot129USDBuy HTTP Debugger Pro

FAQ

- What are the main parts of an HTTP request?

An HTTP request has three parts: a request line containing the method, target URI, and protocol version; header fields carrying metadata such as authentication, content type, and caching directives; and an optional body containing data for write operations.

- What is the difference between GET and POST?

GETretrieves data without side effects and is safe and idempotent.POSTsubmits data that typically creates a resource or triggers server-side processing and is neither safe nor idempotent by default. - What is the difference between PUT and PATCH?

PUTreplaces the entire resource with the provided representation and is idempotent.PATCHapplies a partial update and is not guaranteed to be idempotent unless the patch format supports it. - Can a GET request have a body?

The HTTP specification does not prohibit it, but many servers, proxies, and frameworks ignore or reject a body on

GET. For reliable behavior across all intermediaries, use query parameters or switch toPOST. - Why does my HTTP request return 400 Bad Request?

Common causes include malformed JSON in the body, a missing or incorrect

Hostheader, broken query string encoding, or a body that does not match the declaredContent-Type. Compare the failing request against a known-good one byte by byte to find the difference. - What is an idempotent HTTP request?

An idempotent request produces the same server state whether sent once or multiple times.

GET,PUT,DELETE, andHEADare idempotent by definition.POSTis not, which is why retry logic forPOSTrequires an idempotency key to prevent duplicate side effects.